I spent several hours Sunday night trying to kick-start some creativity. I needed more than just Mr. Sanders to get me moving this time. As I said before, in theory creativity shouldn't be any problem at all. We are by nature creative. Every day every single one of us creates. We aren't handed a script as soon as we crawl out of bed. We create, we improvise, we play off each other. All day. Every day. So what makes the creative arts so difficult sometimes?

I spent several hours Sunday night trying to kick-start some creativity. I needed more than just Mr. Sanders to get me moving this time. As I said before, in theory creativity shouldn't be any problem at all. We are by nature creative. Every day every single one of us creates. We aren't handed a script as soon as we crawl out of bed. We create, we improvise, we play off each other. All day. Every day. So what makes the creative arts so difficult sometimes?

Well, for one, a good story is hopefully a wee bit more interesting than our unscripted lives. Sure, we may create fresh, new dialog during the natural course of our normal day. But it's doubtful we're coming up with anything Shakespearean either. No, to make a good story takes something extra.

A few writers get lucky. Every so often a writer might be sitting on a train and suddenly think, "What about a boy who's a wizard who doesn't know he's a wizard?" I'm not that kind of writer. I struggle; and Sunday evening was no exception. I tried one of my usual tricks (don't ask me why it's "usual" since it hasn't worked yet). I tried to "open my brain" so to speak. I looked at art, listened to music, and did what I could to rise above the reek of the earth into that plane of creative bliss.

Cars are obvious. Humans like to move around a lot and, as a species, we're predisposed to solving problems as quickly and efficiently as possible. So what could be more obvious than inventing an object that moves around under its own power, carries people and cargo, and only costs between ten and ninety percent of each paycheck? If cars had never been invented, it's likely you would have come up with the idea just this morning.

Cars are obvious. Humans like to move around a lot and, as a species, we're predisposed to solving problems as quickly and efficiently as possible. So what could be more obvious than inventing an object that moves around under its own power, carries people and cargo, and only costs between ten and ninety percent of each paycheck? If cars had never been invented, it's likely you would have come up with the idea just this morning. I didn't realize how long it's been since I gave a

I didn't realize how long it's been since I gave a  Romeo and Juliet had name troubles. One of them a Montague and the other a Capulet (or perhaps a Jet and a Shark, if that's more your thing), their love was forbidden by the very labels given to them by their families (or by their toe-tappin', finger-snappin' gangs, if that's more your thing). But Juliet knew. She got it. Juliet knew that a simple label did not define her Romeo. "What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet." Call a rose a pickle, and it would still smell like a rose. The name does not matter.

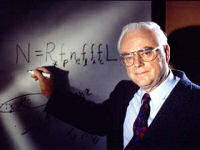

Romeo and Juliet had name troubles. One of them a Montague and the other a Capulet (or perhaps a Jet and a Shark, if that's more your thing), their love was forbidden by the very labels given to them by their families (or by their toe-tappin', finger-snappin' gangs, if that's more your thing). But Juliet knew. She got it. Juliet knew that a simple label did not define her Romeo. "What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet." Call a rose a pickle, and it would still smell like a rose. The name does not matter. If you're a fan of Cosmos or just an astronomy buff in general, then you've surely heard of the Drake Equation. Formulated in 1961 by Dr. Frank Drake, duly pictured here, it's a mathematical equation designed to predict the number of possible extra-terrestrial civilizations out there. It's fairly straightforward. First, figure out the average rate that stars are born. Next, figure what fraction of those might have planets. Now figure how many of those planets can support life. Next, how many of them do support life, and so on. Follow this pattern far enough and eventually the formula tells us how many Frank Drakes there might be in the universe.

If you're a fan of Cosmos or just an astronomy buff in general, then you've surely heard of the Drake Equation. Formulated in 1961 by Dr. Frank Drake, duly pictured here, it's a mathematical equation designed to predict the number of possible extra-terrestrial civilizations out there. It's fairly straightforward. First, figure out the average rate that stars are born. Next, figure what fraction of those might have planets. Now figure how many of those planets can support life. Next, how many of them do support life, and so on. Follow this pattern far enough and eventually the formula tells us how many Frank Drakes there might be in the universe. The current book project is, indeed, intended to be a series of books. When I first re-tooled the idea last summer, it looked like it would span five volumes. While writing the first draft and approaching what would have been the end of the first book, I realized the ending I had originally outlined was fairly lame. Okay, really lame. It would have been as if Tolkien decided to end The Fellowship of the Ring halfway during the Council of Elrond. Had by some miracle it been published, it would have received reviews from some

The current book project is, indeed, intended to be a series of books. When I first re-tooled the idea last summer, it looked like it would span five volumes. While writing the first draft and approaching what would have been the end of the first book, I realized the ending I had originally outlined was fairly lame. Okay, really lame. It would have been as if Tolkien decided to end The Fellowship of the Ring halfway during the Council of Elrond. Had by some miracle it been published, it would have received reviews from some  Two things amazed me about my writing progress last year: 1) that I was actually doing it; and 2) that I managed to write over four hundred pages without even the slightest hint of a plot. This is okay for forty pages or so, you know, just introducing the characters, setting, and what not. Maybe eighty if you're particularly gifted with adjectives. Maybe even two hundred pages, if you have the luxury of forcing all your readers to enjoy your work at gunpoint. But never, ever four hundred pages.

Two things amazed me about my writing progress last year: 1) that I was actually doing it; and 2) that I managed to write over four hundred pages without even the slightest hint of a plot. This is okay for forty pages or so, you know, just introducing the characters, setting, and what not. Maybe eighty if you're particularly gifted with adjectives. Maybe even two hundred pages, if you have the luxury of forcing all your readers to enjoy your work at gunpoint. But never, ever four hundred pages.